2022 ARDHJE Award Finalists’ Exhibition

With artists: Bib Frrokaj, Sead Kazanxhiu, Gerta Xhaferaj dhe Fabiola Skraqi.

September 21, 2022 @ 19:00 – 21:00

@ZETA, Tiranë

2022 ARDHJE Award Winner will be announced during the opening of the exhibition, on September 21, 2022.

The international jury members are: Osmancan Yerebacan, curator and art critic, (USA); Roberto Lacarbunara, Art historian (IT) and Alban Hajdinaj, artist (AL).

The 2022 ARDHJE Award is supported by: Ministry of Culture, Albania; The Trust for Mutual Understanding – New York; YVVA – The Young Visual Artists Awards and Residency Unlimited – New York.

The exhibition of the finalists of the Ardhje Award 2022 will remain open until October 8, 2022.

About the works

Texts by Marko Stamenkoviç, curator of Ardhje Award 2022

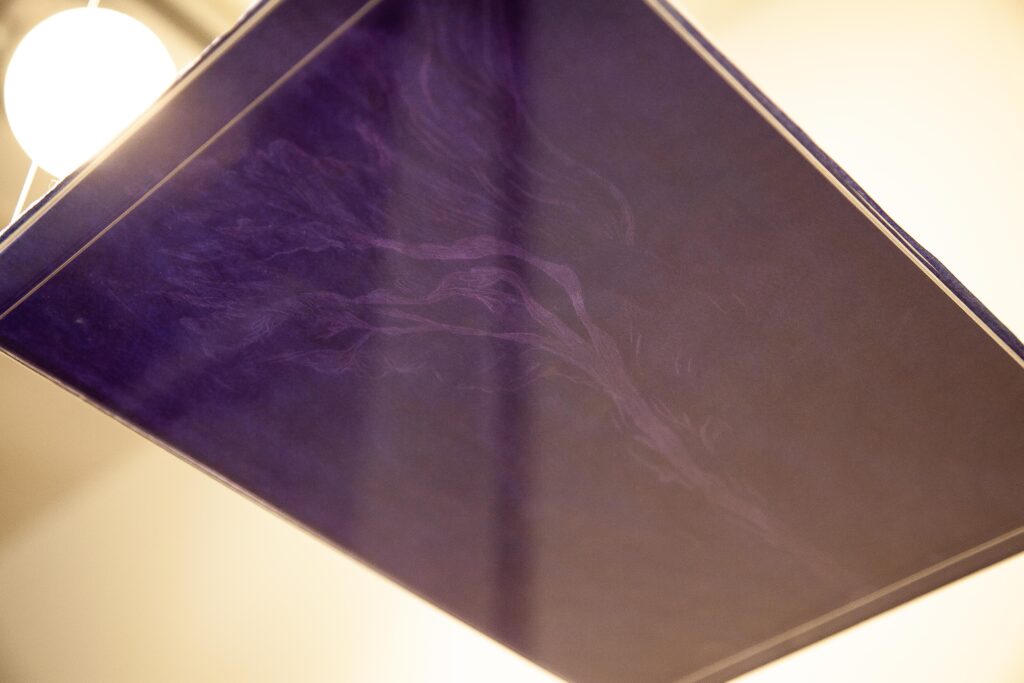

Fabiola SKRAQI

Metamorphosis

Oil on Canvas

Diptych, 100×70 cm/each

2022

In the sphere of Western cultural influences, both in literature and in the visual arts, one myth has contributed to the spread of human awareness of the importance of self-reflective images in the process that played a vital role in the constitution of a modern subject. That same myth left a special influence on the formation of the tradition of autobiographical texts and self-portrait visual representations. It is the myth of Echo and Narcissus, described in the third book of the Metamorphoses, the masterpiece of the Roman poet Ovid from the first century BC – an author who is considered one of the most important poets of the golden age of Roman literature. The narrative of this mythological epic is based on the relationship between a young man and a nymph, that is, a human and a semi-divine being, between whom a situation of (unrequited) love has developed. The beautiful Echo, known for her magnificent voice and singing qualities, falls in love with the equally beautiful Narcissus. However, he rejects her love and redirects it towards an image: the one he sees in the lake at the moment when his own face is reflected on the water’s surface. The phenomenon of modern Subject’s narcissism points out to something very familiar to the twenty-first century’s people: to the global phenomenon of self-mirroring/ selfreflection, this time in the domain of digital technologies and digital communication, with a special emphasis on the emergence of the so-called selfie culture. Selfieculture here refers to the widespread obsession of modern humankind with their own appearance, in terms of self-expression and self-promotion, which is realized through digital photographic self-portraits recorded with mobile phone devices and available on virtual social networks. This is, above all, a visual, psychological and social phenomenon that has become increasingly popular during the last decade under the name selfie, which is indirectly linked to the previously described myth of Echo and Narcissus. In the psychiatric vocabulary, this phenomenon is also associated with the so-called narcissistic personality disorder, characterized by symptoms that include grandiosity, an exaggerated sense of self-importance, and a lack of empathy for other people, and is manifested by longterm patterns of behavior and attitudes that together can cause problems in multiple areas of one’s daily life. Hidden, invisible, and negative consequences of narcissism in the contemporary context of selfieproduction, linked to the notion of visible, external, corporeal “beauty”, are in the background of Fabiola Skraqi’s art practice. Unlike the fashionable over-exposure of one’s physical appearance, she deliberately inverts the common logic of self-reflection in her pursuit of, what she calls, internal landscapes: the microscopic explorations of her oral cavity translated into surreal-looking paintings as a primary medium of expression. Her introspective and process-oriented work is rooted in her personal, traumatic experience of a medical condition to which she was subjected years ago. This implied a six-hour long maxillofacial surgical intervention focused on her oral cavity, which did not only expose her to bodily pain during the time she was lying down over the surgical table, but also to the necessity to put into question her perception of herself and the world around her during the three-year long period she spent recovering from the medical treatment. Over the time of her convalescence, Skraqi approached image-making as a tool efficient enough to help her come to grips with the post-traumatic condition. Initially, she produced a number of selfies, the majority of which were made inside her mouth and throat thanks to her use of a microscopic camera. Later on, she conceived a number of public performances, a sort of communal “rituals” involving visitors to act around the central object on display – a table, reminiscent of her surgical table, but now covered with fruits and vegetables. This is where participants were invited to empathize with her own suffering in a way that may not have appeared obvious at first instance. As a matter of fact, during the time of her rehabilitation, Skraqi was not able to perform naturally her eating habits, given the vestiges of pain inside her body: in other words, swallowing a piece of fruit meant a lot of personal sacrifice for her. This query into the others’ sensitivity towards someone else’s individual experience of physical pain foregrounds her art practice as an ethical activity, where she combines photography, performance, and female body into a set of media tools through which her critical investigation – of the notion of beauty (in relation to personal and social norms and expectations ascribed to it) and transformations aligned with it – evolves at the point of intersection between visual arts, science and nature.

oil on canvas, diptych

100×70 cm/ach,

2022

Gerta XHAFERAJ

Liminal Hymn

Sound installation

(found objects in construction sites: stones, bricks, tiles, wood, iron), 12’58’’

2022

Back in the mid-nineteenth century, during the reign of Napoleon III, Paris – the capital of the Second French Empire – witnessed the beginning of a large-scale project of urban renewal, usually considered as exemplary in the modern European history of architecture. The project was directed by a person appointed by the Emperor himself, who happened to be a highly positioned official with a background in law and music rather than the city planning: Georges-Eugène Haussmann. It is due to his surname that the massive public work program undertaken in 1853, which underwent several stages of development over the next seventeen years, is popularly called the “haussmannization” of Paris. This process brought radical changes to the city’s infrastructure, functioning and appearance, but also to its social fabric; consequently, the lifestyle – of its inhabitants and the increasing number of newcomers – underwent a radical transformation, too. The initial idea was ambitious enough to be conceived as primarily beneficial to the local population, whose high density under unhealthy living conditions (including sanitary problems) urged for rethinking the narrow streets of the medieval-looking Paris, exposed to dirt and disease, from an entirely new perspective that could bring long-lasting effects of urban transformation. The thoroughgoing master-project thus involved construction work on an unprecedented scale, with large boulevards and green areas expanding throughout the city over a network of wider streets and new squares, which led to the alteration of the street plan to the point where Paris stands as we know it today. The flip side of this enormous (and enormously expensive) case of the construction industry in the early modern period was the inevitable price Paris had to pay to be reborn. The systematic demolition of houses and entire neighborhoods, in both central and peripheral areas, necessary for the new urban plan to come about, resulted in the forced displacement of thousands of people and mostly affecting those of a lower social rank. Isn’t it unusual that French impressionists (Haussmann’s contemporaries), who were working in the city and its surroundings during the already developed phase of his project, in the 1870s and 1880s, do not actually expose the underside of Parisian urban progress in their paintings but, fascinated by its surface, rather glorify its brighter, more mundane and glimmering face? Unlike them, Gerta Xhaferaj exposes the darker side of the twenty-first century “haussmannization” of her native Tirana. Strongly informed by her studies of architecture, she merges historical research, found objects and sound into a mixed media installation that questions hybrid cultural identities, value systems, and socio-economic perceptions conditioned by specific locales. In the case of Albania, “delayed” modernity has allowed for its traditional urban settings to remain untouched by grand renewal projects for more than 150 years, if compared with the situation in France under Napoleon III. For better or for worse, over the last two decades things have finally started to change, and they seem to go in many directions and at a fast pace, yet at a precious cost in most of the cases. Tirana, with its chaotic urban pattern that sometimes makes it feel overpopulated, has been a noisy and ever-growing construction site since the early 2000s. Strongly supported by those in power, ambitious to convert a modest city into a metropolitan urban agglomeration inclusive of its impoverished suburbs, as Napoleon III once did, Tirana has been unrestrained in at least two things: on the one hand, showing off the architectural signs of economic progress by erecting business towers and transforming small, old neighborhoods into commercial complex areas; on the other hand, achieving the modernization goals by means of sometimes necessary, but often unscrupulous destruction of existent infrastructure. This, among other cases, implies the demolition of old houses and entire residential zones, as well as the exemplary historical venues that have been categorized, by law, as tangible cultural heritage of the second or third degree. Being sensitive about transformations to which these heritage sites have been exposed over time, Xhaferaj’s project translates the profit-driven redesign of Tirana, noisy as much as destructive, into an aesthetic experience: the one that is able to filter her personal memories into critical and emotional collective sensations. What may at first sight look like a pile of discarded waste (bricks, stones, metal rods, etc.) is, in fact, a memorial: a sort of grave marker made out of vestiges she found and collected next to the demolished buildings. While honoring the cultural significance once attached to them, she is relating to the price that the city has to pay through the sounds of construction/deconstruction of its transformation recorded in their proximity: a mournful anthem for Old Tirana.

Sound installation (found objects in construction sites: stones, brisks, tiles, wood, iron), 12’58”

2022

…

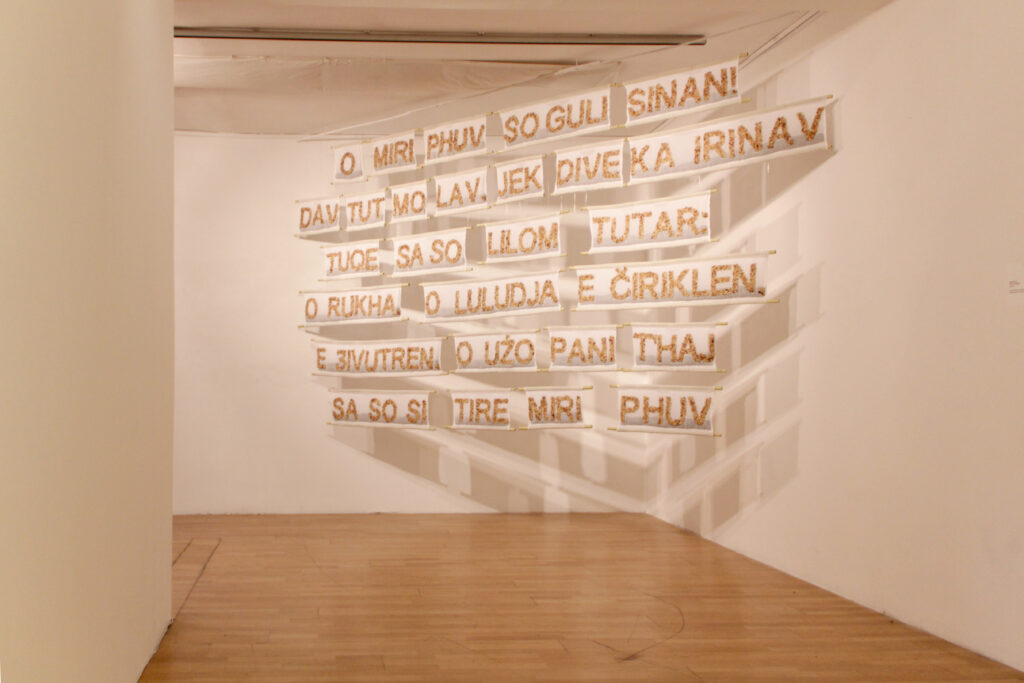

Sead KAZANXHIU

The Eel Line and the Garden of Eden

Installation

(various materials: cherry seeds, textile fabrics, reed sticks), 380x210cm

2022

The Eel Line is the name of a waterway passing through the village of Baltëz in the southwestern Albanian region of Fier. The water reaches the canal from Gjanica, one of the most heavily polluted rivers in the country, which runs through the city of Fier before it joins another, Seman river, and flows into the Adriatic Sea. Over time, Gjanica has earned a bad reputation due to the fact that both urban and industrial wastes keep being discharged into it, without any control or implementation of adequate wastewater treatment by responsible local authorities. The leaching toxic compounds, together with the untreated sewage, pose a serious threat to the natural environment and cause harm to populations inhabiting the area, who mostly (but not exclusively) belong to the minority of Roma and Egyptian communities. Despite their repeated claims for the situation to be taken into more serious consideration, both younger and older generations of residents have been suffering for years, without having any constructive response from the competent entities of the local municipality. In recent years, water pollution – which, in turn, produces unbearable odors and air pollution in the village of Baltëz – has been evaluated as the major cause of various diseases in this area, such as bronchial asthma or various types of allergies. What once used to be a fishing ground has turned into a poisonous playground for mosquitoes, the impact of which – to the health condition of people living in its immediate vicinity – is incommensurable when it comes to infections the insects are causing. Will it ever be possible to transform these unfavorable conditions into better ones, making Baltëz a healthier place to live? This was a starting question that has led Sead Kazanxhiu into a new project, which addresses the environmental micro-catastrophe of his native region from a very personal perspective. Given the fact that his family members, alongside other members of the local Roma community, share the land through which the Eel Line passes, their exposure to unhealthy living conditions affects him both emotionally and ethically. On the one hand, what does it mean for the local public administration to ignore repeated emergency requests for introducing water recycling facilities, so water waste could be eliminated at last? On the other hand, what does it mean for local residents – who happen to be treated as “human waste” – to have their protest notes constantly unacknowledged by those in charge and whose alarming voices are refused to be heard? Perhaps intentionally? Perhaps because some of them are only “gypsies”? This popular though derogatory term calls upon the significance of language, both spoken and written, for the context out of which Kazanxhiu’s project emerges. However, the aim of it is not to create yet another form of complaint. The questions of race, ethnicity and social exclusion are here subtly woven together with the concerns for health and ecology, for which Kazanxhiu makes not only a symbolic but also pragmatic proposal. By introducing the question of economy, or the question of economic selfsustainability, he gives his own, very concrete example about the personal responsibility one may need to involve in the given public discussion (or its lack thereof) while providing necessary visibility to what tends to be disregarded or hidden from public view. To undertake such a step, he may have been encouraged by successful earlier examples of ecosystem restoration projects elsewhere, one of them being the worldwide known case of the forest revival in Brazil: it is the outcome of a long personal commitment of the photographer Sebastião Salgado and his wife, who have planted – over two decades – two million seedlings of various trees each year, thus turning the formerly barren land, where used to be a forest during Selgado’s childhood, into a reborn green oasis. Despite the low-grade water quality in the Eel Line, Kazanxhiu has approached his own piece of land as a fertile ground, where it is still possible to cultivate plants and open the way to organic farming. He opted for fruit trees, whose fragrance – when they are in full bloom – becomes a tool to fight back against the harming conditions of environmental pollution (and the intolerably bad smell stemming from it). In the tradition of olfactory art forms that use scents as a medium – and where human nose plays equally important role of perception as the eyes do, Kazanxhiu first collected the seeds of various fruit trees as samples of seedlings he had already planted on his land in Baltëz, acting according to his own will and independently, in pursuit of self-sustainable ecological and economic solutions. Then he arranged them into a three-dimensional message form, the one that turns his artwork into a promise – a personal obligation towards his own community – pronounced, therefore, in Romani language: “O my land, how sweet you are! I promise that one day I will return all what I took from you: the trees, the flowers, the animals, the birds, the clear water and everything that belongs to you, my land!” It may take time before his promise becomes fulfilled: what matters now is that Kazanxhiu has made an important, transformative step forward towards his own “Garden of Eden”. Smell it!

Installation (various materials: cherry seeds, textile fabrics, reed sticks), 380×210 cm

2022

…

Bib FRROKAJ

The Hidden Mountains of Mat River

Installation/Mixed media

(video animation 38’’, drawing on paper 430x137cm, carbon copy paper 21x30cm/4 pieces)

2020-2022

The ancient Sumerians, whose civilization thrived in the fourth millennium BCE in what is nowadays southern Iraq, are of great renown in history thanks to the unprecedented legacy they left behind. Besides their city-states, the earliest complex urban societies in the world that they established between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and the invention of writing (among other achievements), their fame is also associated with their religious architecture built out of mud bricks. Their temples were standing atop high platforms known as ziggurats, thus forming monumental terraced structures composed of several levels receding one after another from the bottom up. Dedicated to each city-state’s respective patron God, they were considered as “waiting rooms’’ where, according to their beliefs, the deity would descend from the heavens to appear before the priests in the central hall of a temple. In other words, they served as intermediary communication spots for priests through which the picture of the Sumerian world was created by their Gods’ representatives on Earth upon two opposite perspectives: a bird’s-eye view on behalf of deities and a frog’s-eye view on behalf of humans. The excavations that led to their discovery in the 19th century must have left archeologists astonished. Likewise, when in 2020, during the initial phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, Bib Frrokaj first spotted odd ziggurat-like forms along the river passing through his native area in the northwest of Albania, it was out of mere astonishment that the idea for his new project got born. The initial phase of his research was forced to remain remote, due to the government-imposed lockdown measures and his inability to directly approach strange structures reminding him of dunes. Thanks to his access to new technologies, he first used the Google Maps application as a satellite-based tool that enabled him to visually navigate the physically inaccessible field over the Internet. Inspired by imagery shot by satellites, he referred to it as the basic preparatory material for sketching a series of small drawings and watercolors. For him, this felt like gaining access to the extraordinary ways that potential aliens from the outer space (or Sumerian Gods, even) would have perceived his own neighborhood. Moreover, while making his drawings after satellite images and their unusual, twisted perspective upon the “dunes”, he felt like an alien himself. When he was finally able to visit what he sometimes prefers to call artificial mountains, it became clear that, meanwhile, many construction facilities had been built along the entire river in order to collect and use sand from it, which in turn resulted in the creation of massive man-made dunes. Apart from their everchanging shapes, which keeps fascinating Frrokaj, the darker side of the phenomenon lies in the fact that the extraction and accumulation of sand negatively affects living conditions of this area’s inhabitants, as well as the natural habitat, now prone to destruction. Aware of the public negligence of the issue and the lack of media interest in it, Frrokaj was even more eager to continue with his visual experiments, especially now that he was also able to make drawings of the “dunes“ from the human’s-eye perspective – and to compare them with those earlier inspired by machine-made views. More than two years of his research process resulted in a mixed media work that combines satellite photos, digital photography, small and large scale drawings, watercolor images, and video animation. The usage of various media focused on the same subject does not only contribute to the multiplication of views, but also to the pluralization of worldviews onto the easily ignored point of discussion (industrial exploitation and degradation of nature), in dire need for articulation – and visualization – in the public sphere. Otherwise, the hidden mountains of Mat river will remain to recall the Sumerian “waiting rooms”, with no intermediary between the celestial and earthly beings, apart from a single visual artist calling his fellow countrymen into attention and solidarity – before it is too late.

Installation/Mixed media

(videoanimation 38″, drawing on paper 430×137 cm, carbon copy paper 21×30 cm/4 pieces)

2020-2022

Find out more about artists here:

FABIOLA SKRAQI (*1993, Lushnje, Albania) is a visual artist who lives and works in Milan, Italy.

She studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts Brera in Milan, where she received her Bachelor degree (2018) and Master degree (2021). Meanwhile, she also took part in two academic exchange programs in Belgium and France, respectively: at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Liège (2019), and the University of Paris 8, Vincennes – Saint-Denis (2020).

Her solo exhibitions include: Ce Soir On Danse #6, MIMA, The Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art, Brussels (2018), and Metamorphosis, Little Red Bird Gallery, Millerton, New York (2017). Her work has also been presented in group exhibitions in Italy, Belgium, and Bulgaria. They include: DIS-Parità, Castello Sforzesco, Vigevano/Pavia (2022); Walk-In Studio, Festival of artistic studios, Milan (2021); The Distance Between Insanity and Genius Is Measured Only By Success, Espace Moss, Brussels (2019); Diario Naturale, Lawyalty – Avvocati Associati, Milan (2019); What now/Now what, Sofia Underground – International Festival of Performative Arts, Sofia (2018); Hide & Seek, 17th Pink Screens – Queer Film Festival, Cinema Nova,Brussels (2018); and Selfie, Osservatorio 9, Palazzo Mandelli, Arena Po/Pavia (2017). In 2018, she realized Ring, a performance in collaboration with Lie-fi Palimpsest collective, in the framework of Supermarket – Stockholm Independent Art Fair.

BIB FRROKAJ (*1992, Lezhë, Albania) is a visual artist and art educator who lives and works in Lezhë.

He is a holder of MSc degree in painting, obtained in 2016 from the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Arts in Tirana. Prior to this, he studied graphic arts at the University “Luigj Gurakuqi” in Shkodër, where he earned his bachelor degree in 2014. Upon his formal education, he was involved as an official photographer and marketing consultant for the fashion & design studio GADOV Atelier in his hometown, and since 2017 he has been working as a full-time visual art teacher at an elementary school in Lezhë.

Apart from his solo exhibition The Long Wait, held in 2021 at the Layer House – Layerjeva hiša in Kranj, Slovenia (in the framework of the Kranj Foto Fest), ever since 2014 he has taken part in a number of group exhibitions in Albania and the neighboring countries (Kosovo, Serbia, Montenegro). His most recent group shows include Given, organized by foundation17 at Kino-Rinia, Pristina (2020), ARDHJE, 12th Edition of Young Visual Artists Award Finalists, ZETA Contemporary Art Center, Tirana (2020), Seven Albanian Photographers. One Residency, Marubi Museum of Photography, Shkodër (2019), 30YearsOld, FAB Gallery, Tirana (2019), 5th IDROMENO Award, City Gallery of Arts, Shkodër (2017) and Regard Sur Mon Voisin – View on my Neighbor, The French Institute Gallery, Belgrade, and Petrović Palace, Podgorica (2017).

Since 2016 he has also taken part in several artist in residence programs, such as Infrared, foundation 17, Pristina (2020), Art House Residence, Art House, Shkodër (2019), Regard Sur Mon Voisin: Photography Artists Residency, Montenegro/Bosnia & Hercegovina (2017), and Cittadellarte, Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella (2016).

Since 2013 he has been invited to take part in numerous artistic workshops and professional training programs, such as Fleeting Drawing, Harabel Contemporary Art Platform, Tirana (2018), Photography as a tool of encounters, Salzburg Academy Summer School, Salzburg (2016), Summer School as School, Station – Center for Contemporary Art, Pristina (2015), Resolving Post-Conflictual Situations Through Visual Arts, The Romanian Independent Film Association (ARFI), Timisoara (2015), and Art, Plastic and Recycling, IPA Cross –Border Program Albania-Montenegro, Cetinje (2013).

He has been selected two times as one of the finalists for the ARDHJE Award for the Young Visual Artist of Albania (2022 and 2020), as well as for the PreFoto Photography Competition in Preševo (2016 and 2015). In 2017 his photographs entered the list of top 30 at the 17th edition of Urban Photo Fest in London, while in 2015 in Tirana he won the first prize for Shkrepe – National Competition in Photography.

GERTA XHAFERAJ (*1993, Fier, Albania) is an architect and visual artist who lives and works in Tirana.

She studied architecture at Epoka University in Tirana, where she received her MSc. degree in 2017. She is currently pursuing an MA program in Fine Arts at the FHNW University of Art and Design in Basel. In 2021 she took part in the international educational program Summer School as School, organized by Stacion – Center for Contemporary Art Prishtina.

Her selected group exhibitions include: Necrography, Grand Hotel, Manifesta Biennal 14, Prishtina; Nepotik, Boulevard Art Media Institute, Tirana (2022); Reframing History, Vogue Photo Festival, Vid Foundation, Milan (2021); KULA A, Virtual Exhibition, Ecumene Residence, Bologna (2021); M Club, Galeria 17, Prishtina (2021); Necrography, Bazament Art Space, Tirana (2021); Nepotik_Instant Photo, Bazament Art Space, Tirana (2020); Sazan: No man’s land, Galeria e Bregdetit, Vlora (2019); and The Balkan Girl Power, COD – Center for Openness and Dialogue, Tirana (2018).

She has attended artist-in-residence programs organized by Footnote Centre for Image and Text in Belgrade (2022) and Galeria e Bregdetit in Vlora (2019).

She is a 2022 winner of the VID Grant Financial Prize by the VID Foundation for Photography, Amsterdam.

SEAD KAZANXHIU (*1987, Baltëz/Fier, Albania) is a visual artist and activist who lives and works in Tirana. He studied painting at the University of Fine Arts in Tirana, where he received his Bachelor degree in 2010. Between 2011 and 2012 he attended the Central European University in Budapest, where he took part in its Roma English Language Program, and between 2018 and 2019 he attended the Albanian School of Political Studies. Since 2019 he has been an active member of PAKIV Board of the European Roma Institute of Arts and Culture (ERIAC).

His selected solo exhibitions include: Paramisa Othe Sastipe Akate/Fairy tales there, health with us!, Studio Capitol, Tirana (2020); Dislocation, Regional Cooperation Council & Roma Integration, Swissotel, Sarajevo (2019); Në Oxhakun Tim/Next to my chimney, Zeta Contemporary Art Center, Tirana (2018); Perpetuum Mobile, Tulla Culture Center, Tirana (2016); Vendi im/My Place, National Historical Museum, Tirana (2014); Model, The European Parliament Main Hall, Brussels (2014); Roma Monument, Ministry of Social Welfare and Youth, Tirana (2013); 8 FOR 8 OF APRIL, Albanian National Parliament, Tirana (2013); and Model, Central European University, Budapest (2012).

He has presented his work in numerous group exhibitions, including: One Day We Shall Celebrate Again: RomaMoMA at documenta fifteen, Fridericianum, Kassel (2022); We are Here! – The 2nd Roma Biennale (2021); South by the sea, Galeria Bregdetit, Vlora (2020); Keres kultura/We create culture (Contemporary Art and Roma Identity), The Central Slovak Gallery, Banská Bystrica (2019); You are not like them you are like us: 1000 Years of Roma History, Art Turbina, Tirana (2018); Gypsyism Balkanism – Uniting Peripheries, ERIAC, European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture, Berlin (2018); The Roma Spring: Art as Resistance, ERIAC, European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture, Berlin (2018); MOCAfest: Marketplace of Creative Arts, International Art Festival, Borneo Convention Centre Kuching, Sarawak (2017); The Future of Borders: Autostrada Biennale, Prizren (2017); Transgressing the Past Shaping the Future, Federal Foreign Office, Berlin (2017); Home: Mediterranea 18 Young Artists Biennale, Tirana (2017); Under Chaotic Silence, Richter Gallery, Den Helder (2017); (Re)Conceptualizing Roma Resistance, Goethe-Institute, Prague and HELLERAU – European Centre for the Arts, Dresden

(2016); SiO2 – The Reason of Fragility: Contemporary Artists Facing Glass, ONUFRI Prize XXI, National Gallery, Tirana (2015); Gipsy Under Erasure, GIBCA, Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (2015); Do Not Tell Us Who We Are, Pakivalo Festival, Romano ButiQ, Bucharest (2015); Erasure, National Historical Museum of Albania, Tirana (2014); and Third Symposium, Museum of Roma Culture, Brno (2012).

He was invited to artist-in-residence programs by TICA Tirana (2018), Richter Gallery, Den Helder (2017), and Jaw Dikh Art Colony, Czarna Góra (2011, 2010). His most recent publication was Paramisa Othe Sastipe Akate: Graphic Novels with Rromani Fairy Tales and Legends (2020).

About the Jury:

Osman Can YEREBAKAN is a curator and art writer based in New York. His writing has appeared on T: The New York Times Style Magazine, The Paris Review, Vulture and The Cut (both New York Magazine), The Brooklyn Rail (the most recent interview with Ian Cheng), BOMB, Village Voice, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, L’Officiel, Flaunt, Galerie Magazine, Cultured, and elsewhere.

Osman previously organized exhibitions at The Clemente Center (Residual Impression; A Room of One’s Own), La MaMa Galleria (Party Out Of Bounds: Nightlife As Activism Since 1980), Radiator Gallery (Works: Reflections on Failure), Equity Gallery (Like Smoke), AC Institute (My Nights Are More Beautiful Than Your Days), Center for Book Arts (En Masse: Books Orchestrated), Local Project (Hopscotch), UrbanGlass (Glass Ceiling: Art of Resilience and Fragility), Leslie Lohman Museum Project Space (Alternate Routes), and, most recently, at the Queens Museum (Executive (Dis)Order: Art, Displacement & the Ban).

Alban HAJDINAJ studied graphics at the Academy of Arts in Tirana Albania. Worked as researcher at the National Gallery of Arts in Tirana Albania. His works have been exhibited at Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art (Budapest); Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris); International Studio & Curatorial Program (New York); Mart, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Trento and Rovereto); Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin); 52nd Venice Biennale (Albanian Pavilion); Chelsea Art Museum (New York); Moderna Galerija (Ljubljana); National Gallery of Kosovo; National Gallery of Arts (Tirana); Sammlung Essl, Klosterneuburg (Viena); Manifesta 4” (Frankfurt/Mein); IFA Gallery (Berlin /Bon) and Tirana Biennale 1.

Hajdinaj’s works are also part of public collections such as: Musée National d’Art Moderne (Centre George Pompidou), Paris; Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest; Peter und Irene Ludwig Foundation; National Gallery of Arts, Tirana; FMAC Paris; Zabludowicz Collection London; Kadist Foundation, Paris.

Roberto LACARBUNARA, journalist and contemporary art curator, lives and works in Italy. He is the Art Director of the CRAC Museum – Centro Ricerca Arte Contemporanea in Taranto and associate curator at the Pino Pascali Foundation in Polignano a Mare. He is Professor of Contemporary Art History at the Fine Art Academy in Lecce. Recent essays and monographs include: “Passages / Paysages” (Mimesis, Rome, 2022), “Fondazione Biscozzi Rimbaud. Una Collezione” (Silvana Editoriale, Milan, 2020); “Pino Pascali. From Image to Shape”, Exhibition catalogue at the 58th Venice Art Biennale 2019; “Pino Pascali. Fotografie” (Postmedia Books, Milan, 2018), “Super. Pino Pascali e il sogno americano” (Skira, Milan 2018). He cooperates with the national daily journal La Repubblica and the monthly journal Espoarte.

…

*The ARDHJE Award is an international prize for contemporary visual artists from Albania, initiated by TICA-Tirana Institute of Contemporary Art, in 2005 and joined the regional network YVVA – The Young Visual Artists Awards in Central and South Eastern Europe in 2007.

ARDHJE is an annual competition and award, aimed at promoting creativity, public exposure, and contemporary art in Albania and internationally.

ARDHJE Award, as well as similar prizes in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, is conceived as an open competition addressing young artists of Albanian origin up to 35 years of age to apply and take part in a transparent process, that does not only offer the opportunity to create new works and present them at a group exhibition of selected finalists, but also to support their artistic and professional development. A jury, composed of local and international experts in the field, selects 4 finalists, who are provided with an allocated production budget, the curator and the exhibition venue in Tirana. Jury’s decision about the winner depends on the candidate’s artistic merits and prominence demonstrated by the artistic portfolio and CV; the particular artwork presented at the finalist exhibition; the results of an interview with the international jury; and the potential to benefit from immersing oneself into the New York art scene during a two-month stay at Residency Unlimited.