ZETA Contemporary Art Center

presents:

BAST | Bet on the Future

a one day unexhibition by Armando Lulaj

“Art is a very long game. An endless vortex, a torture game. You can play the game or let go. The decision is to be made as soon as possible.” (AL: 13.04.2025)

The Wager

a curatorial speculation by Pedro Royo

“All tomorrow’s parties are happening in Albania”: that is what a friend texted me as I boarded the plane for Tirana. I had been waiting for a few hours at the gate after some of the inevitable delays that always crop up when one is flying somewhere that only a select few are in a hurry to get to. This friend – who shall remain anonymous for the time being – told me “The art scene there – once upon a time, they were the New Prolets of the Art World. Now they are its DJs.” To be honest, after some hours spent waiting amidst a sea of disgruntled passengers in VIE, listening to grumbling grandmothers and bored backpackers, I was looking for that kind of cathartic energy: the prolet-turned-DJ, the future artist of the Balkans? What a vision.

I have to admit, as I write these words, that I’m not entirely sure what I was seeking in Albania. I planned this trip simply because so many had told me about this cultural gem of the Western Balkans – gemlike not only because of its stunning nature, but even more so because of the vibrancy of its art scene, one that (by all accounts) is now in the throes of giving birth to something definitively new. Might I arrive in time to witness this birth? Would I be able to glimpse anything of the old world? These were open questions to me: what thrilled me about this trip was precisely the chance to observe a definitive transformation rising up from the margins of Europe, which is now so mired in turmoil and settling into its old ways again. (Someone on the plane VIE – TIA was reading a copy of Forbes with Albania’s first billionaire on the cover. Does he buy art, I wonder? Later I found out he does, and even finances a contemporary art gallery. I had packed Lea Ypi’s popular book Free – so celebrated in Albania and beyond – but I am embarrassed to say it stayed in my luggage throughout the entire week I spent in Tirana. But the kind of reckoning with the Albanian communist past that I witnessed on this journey made me eager for its insights.) I was looking for a way-station, one abundant in something that could be useful as fuel, burning and fuming: coming of age with the art of tomorrow.

And it is undeniable that Albania seems to play host to such a catalyst. I felt it from the moment I stepped off the plane: a kind of anticipation, boiling up in the interstitia of consciousness like a slow-building storm that’s still out of sight but you feel it in the atmosphere. Maybe the rugged mountain skyline along the northern edge of the city contributed to it, or maybe it was the long and careening ride from the airport into the city center of Tirana that made me really feel it in my gut. In the gorges, indeed. Sometime in the late 90s people were talking about the time of ironic optimism, but I think that optimism is very real now – it’s here, almost effervescent.

My taxi driver into the city, weaving around other cars at a breakneck pace, quickly determined that I had never been to Albania before, and decided it was his duty – as good taxi drivers will – to educate me. He rattled off a long list of infrastructural and architectural changes almost faster than I could take note of them. He seemed most emphatic about the buildings: “Big heads! Big eyes! The eyes of Tirana!” he shouted as he gestured wildly. “They are really building something now, these guys. They have a vision!” I admit, it was hard to get a glimpse of that vision until we slowed a bit in the heart of the city, where every street seems to be overgrown by a forest of towers: brand new apartment buildings that would be the envy of the citizens in capital cities across Europe, much less where I was born. And there is no want for variety: one building looks like the head of the national hero, Skanderbeg (looking out over a stunning new square that also bears his name), while another has a relief map of Albania protruding from its facade. Mere kitsch? Perhaps, but a kitsch that leads, rather than following behind populist sentimentality.

“These guys” – to whom my driver referred – includes, above all, Edi Rama, the giant (I am being quite literal, he towers in his gleaming white basketball shoes) who serves officially as Albania’s Prime Minister and semi-officially as its artist-in-chief. Back in the 2000s, when Rama was mayor of Tirana, he launched a campaign to paint the grim, grey concrete apartment buildings built during the communist regime in bright colors and vibrant geometric forms, transforming the city into a kind of Constructivist utopia. The European funders at the time hated it, but Rama persisted, and eventually this project got the attention of some major curators, people who understood the power of what he was doing. Now, decades later, Rama has brought that vision to the leadership of the Albanian state – he has been Prime Minister since 2013, producing perhaps the first truly “artist-run country” in the world. His work has been in the Centre Pompidou, and at Venice (part of the astounding tour de force that was Viva Arte Viva), and one imagines that his vision for bringing together art and politics will make its way into the great narratives of 21st-century art. There are many who already put his name down alongside the most transformative artists of the postwar period. He has even made Albania’s prime ministerial building into an art gallery, and now plans to establish a foundation to preserve his legacy and work. Eventually, one imagines that even the smallest village of Albania will have its own contemporary art space: art will flow like water. (I must disclose that while I have never met Rama, a mutual friend put me in touch with him. While he could not meet me while I was in Tirana, he secured me lodging in the presidential palace and even offered me a government villa along the southern coast as a writing retreat – an offer I could not take him up on this time, but I will certainly return.)

If Rama’s visionary leadership alone wasn’t enough to convince me that something important is happening in Albania, the buzzing amongst the members of the art scene there confirmed my hunch. Everywhere I went, artists and their circles seemed sure of one thing: the future’s looking bright; the country is a lightning field of starting points. Everyone seemed to be talking about two places, the Factory and the Station. The Factory: an effort to reconstruct Warhol’s vision – up north, I gather, outside of the typical orbit. The Station is somewhere here in Tirana, but when I asked about it, people just started laughing and said I was already there. I suppose that’s the point: Albania’s artists are finally embracing their destiny: while the rest of the world hurtles towards fascism at a dizzying pace, this is one of the last places where one can be ecstatic to be an artist.

For the time being, the National Gallery is closed for renovations, but even that feels symbolic: there’s little enough that matters from the past when the future promises so much. Would halls hung with Socialist Realism (which I understand constitutes most of the National Gallery’s collection) really help anyone navigate the world today? I understand that when it reopens, it will be with a rather more spectacular architecture and mission. When it comes to contemporary art, there are plenty of initiatives: there’s Harabel (named after a bird, and apparently taking a well-deserved break from programming during the period I was in town), and GOCAT (the acronym means ‘Gallery of Contemporary Art Tirana’ but it also spells out the Albanian word for ‘the girls’ – delightful), opened by the billionaire I mentioned before. The latter is located inside of the Pyramid, a vast and recently renovated structure that used to house a museum to Albania’s communist dictator, Enver Hoxha. Where else could such a profound re-imagining of the past receive both political and private support? It’s hard not to feel a slight jealousy about the plethora of opportunities opening up in Albania. (There’s even an art cruise ship, I was told.)

Hoxha might have ruled this country brutally for more than forty years (“with an iron fist” is how all the journalists have put it), keeping Albania isolated from the rest of the world for the sake of some Stalinist vision, but today his former villa – located in the stylish Blloku neighborhood – has been transformed. Like the Pyramid, the new villa (Vila 31 they call it) is a brilliant gesture in overcoming the past, facing it head on and refusing to blink. In the time I was in Tirana, this villa opened to the public for the first time since communism – and didn’t just open, but opened with a truly utopian vision, comprising a stunning array of arts events: open studios; performances; an exhibition exploring the experiences of those persecuted by the communist regime, framed through an encounter with Nelson Mandela; and, of course, a prodigious roster of concerts and DJ sets. It was incredible to see the Albanian scene pack more culture into just a few days than most major biennials and festivals manage to muster over weeks and months, despite their massive budgets and much greater notoriety.

While at this villa, a couple of local artists regaled me with Albanian folk tales about snakes and fireflies – apparently, these kinds of stories still circulate in the Albanian lifeblood, and they certainly add to the rather mysterious allure that the whole event exercised upon my imagination. The old Albanian honor code insists that the friend is met with “bread, salt, and heart,” and something of this powerful welcoming spirit lives on. The “blood and honey” that inspired the first curatorial engagements with this region now runs over, like a fountain: this is an artworld that is in love with its abundance, an accelerationist Eden. It wasn’t only artists who seemed moved by this radical optimism: I met many foreign curators (and of course collectors) – like myself, visiting Tirana for just a short time – who told me they were quite certain that Albania now plays a decisive role in the direction of global contemporary art. (Some had a rather more eccentric view: at one of these gatherings, I even met a curator obsessed with the figure of Valerie Solanas – she refused to meet with any artists, or to speak about anything except some Albanian-language remake of Mary Harron’s 1996 film, which she insisted was the only cultural event that mattered. This film, she insisted, would document the future actions of an artist who would shoot the prime minister, Albania’s own Solanas – someone playing with the medium of the bullet. Many present were horrified by the suggestion; they laughed it off, but I could not shake the image.)

Indeed, not everyone believes in this Eden: there are some artists, apparently, who have been trying to build some kind of a prison inside of a gallery, and others who have been at work beneath the streets, digging underground (I could not quite make sense of this), perhaps building tunnels. These strange rumors seemed only peripheral to the enthusiasm I heard from artists at this Vila 31, who seemed not to want to talk about these other practices. But when I visit a country, I try to meet everyone – even the people no one wants to talk about – and I did make some effort to meet these artists. Ultimately I could not find a way to get in touch with all of them – maybe that is the point. In any case, I did eventually get in contact with a photographer who had recently finished shooting a project for Armando Lulaj, the author of the exhibition in which you now find yourself.

This photographer insisted that I speak with Lulaj, that I find out about his project – which he described to me as “a bet on the future.” Others warned me in no uncertain terms that I should be on my guard: “This is the kind of artist,” someone told me, “who sends bullets to curators.” (Maybe he knew the curator I met earlier, the one obsessed with Albania’s own Solanas.) When I looked into Lulaj’s background, I became a bit concerned about what this meeting might entail, at least for me as a curator: this was an artist who urinated in the middle of Skanderbeg Square – that rather glorious post-historical city center I mentioned earlier – and who had gotten expelled from art school for some disturbing and extravagant performance: wearing a military camouflage outfit, he climbed up and walked around atop of the glass dome protecting Michelangelo’s David in Florence, trying to get his fellow art students to come join him. This sounded like the kind of person – I will be frank – who is difficult to work with, but nonetheless I became increasingly intrigued by this artist that some people described as a “priest” or a “ghost,” and whom still others called a “villain.”

I first tried to track Lulaj down at one of the art spaces he supposedly frequented, but the space was deserted and the only person there was a young man (an intern from Paris) who could not tell me Lulaj’s whereabouts, but who reminded me that Lulaj had been in Venice himself, not in the time of ironic optimism but many years later. Indeed, as this young man unfolded the story I began putting it together, for in fact Lulaj’s had been a decidedly memorable pavilion: a peculiar time capsule housed inside the skeleton of a whale, with 71 volumes of the Albanian dictator’s writings housing their own skeletal appendages. It was as if the pavilion was taken back in time, back to the 1960s: restaging a history that had never happened, until then. Another element of the pavilion involved a great act of rewriting, working on the sides of a mountain. These were striking memories, and I decided that I simply had to meet this artist – but I was told he would not go to the dictator’s villa, a place to which I’d been returning regularly. (He regards the structure as too delicate, possessing the kind of history that one can touch only after one has searched around for its most secret keys – one of which he apparently has in his possession.)

Eventually, our mutual friend the photographer gave me Lulaj’s WhatsApp contact, and although I did not expect him to respond, I was quite intrigued when he agreed to meet me. Lulaj sent a location with coordinates, somewhere he called “Gjiri i Kurvave,” which turned out to be a pleasant part of the forest in the park near Tirana’s artificial lake. Later someone told me that in the past (during fascism) people would go to this spot to meet prostitutes, and later (during communism) lovers met there away from the watchful eyes of the regime. I suspect Lulaj was pulling a bit of a joke on me. But in person I found him surprisingly (as some had told me) like a monk. I started off rambling about everything I had seen at Vila 31, about this incredible transfiguration of history, and about the sincere energy I felt from many young artists in Albania. He listened very patiently, but only smiled and told me “contemporary art in this country is nothing more than an exchange of mirrors.”

I couldn’t quite understand this perspective at first – my head was still swimming with what I had seen in Albania so far, what looked like a blueprint for new forms of artistic agency, for a productive fusion of art and politics that could resist the populism sweeping so much of the world. I told him about the nightingales and the sparrows; about how interesting it was that the office of the prime minister is now his studio; about how artists have organized into a kind of union, representing their own interests to the government. I told him all the good things I had heard from colleagues abroad about their collaborations with the wife of Tirana’s current mayor – who gave up being a lawyer to become a curator – and about how much of an impression the artist-prime-minister has made on the international biennial circuit. Albania was, for me, a breath of fresh air, I told him, a little anxious to convey the urgency of my enthusiasm. “That is all well and good, but I am interested in a different kind of breathing,” he said. As we had walked through the park, we had made our way along a path and now stood near some kind of simple memorial, probably from the time of communism.

He told me, in fact, that this memorial was dedicated to a group of antifascist youth, and that group served as the namesake for another group of artists, one with whom he was closely involved. Many of this group, including Lulaj himself, had been doing a kind of obscure work since the early 2000s, talking about the ways art became intertwined with politics, about power and borders and the margins of society, about Albania in the neo-colonial geography of the world. But there had been a kind of gap, a break, between those early actions, and maybe Lulaj was the one who could connect those struggles to the present. Over the years, this group occupied different conceptual and real spaces, and its membership changed – and then recently it had emerged anew, in full force now, with a kind of manifesto about contemporary art and society in Albania (I remember seeing this on e-flux), and even with a ‘five-year plan.’ Far from the institutional security of the Factory and the Station, Lulaj told me, these people are working to expose the grim reality of another ‘factory,’ one driven by the corrupt circulation of money (I even learned that some big cartels back in my home country had a hand in this circulation). This other factory is not so visible from the villa of the dictator, he explained – even if you are very close to it there, it is harder to see.

This group Lulaj described, which now calls itself Manifesto, a name that declares declaration itself, engages in actions that are sometimes inscrutable: they fill galleries with the residue of demolished buildings, or make them echo with voices that call for desertion. They re-stage photographs and paintings, and reify the tongues of whistleblowers in ice. This group includes not just artists, but critics and historians and publishers and programmers, and they are not only from Albania, but from the Netherlands, the United States, Germany, Italy, and Colombia. They have started talking about their actions – their ideas, their visions – as a ‘Great Wave.’

This sounded a bit sensationalist to me at the time, but hearing Lulaj discuss it made me wonder if there might be something to this whole play with invisibility, creating a kind of haunting presence in the artworld here. I asked if I could see the studios of this group and he said that they didn’t have studios per se – but I might find them in universities and research institutes (where some of them work), but also traversing the streets, or the periphery of the city, in zones of development where new luxury apartment buildings will soon be built. They might be found in night markets searching through the castoffs from embassies, or deep in the archives, or roaming in the hills of Surrel reciting strange magic spells, he told me. In these places, they are at work on writing another narrative, or more precisely other narratives: other versions of a story that I thought I knew quite well. There is an intellectual force to their project that is unlike anything else in the art scene, he insisted. “It’s not that you won’t meet them – you might, but then something very important will have changed.” When I asked him what he meant, he first just shook his head, and then asked me if I would take him up on a bet.

“What bet?” I asked, but he waved off the question. Instead he proceeded to tell me about the project, the one you see today, on Election Day. The wager – well, I don’t know if I took the wager or not, but I believe I did, and it is somehow here, in this space. You are reading these words some weeks after I met Lulaj, and now I have left Albania (though I do hope to return). But for you: for all of you who are now standing here, for those following a path of light and looking at a pile of posters on the floor of a galley while elsewhere citizens of Albania are busying themselves with voting – let me now try to shed some clarity on the wager Lulaj puts forward.

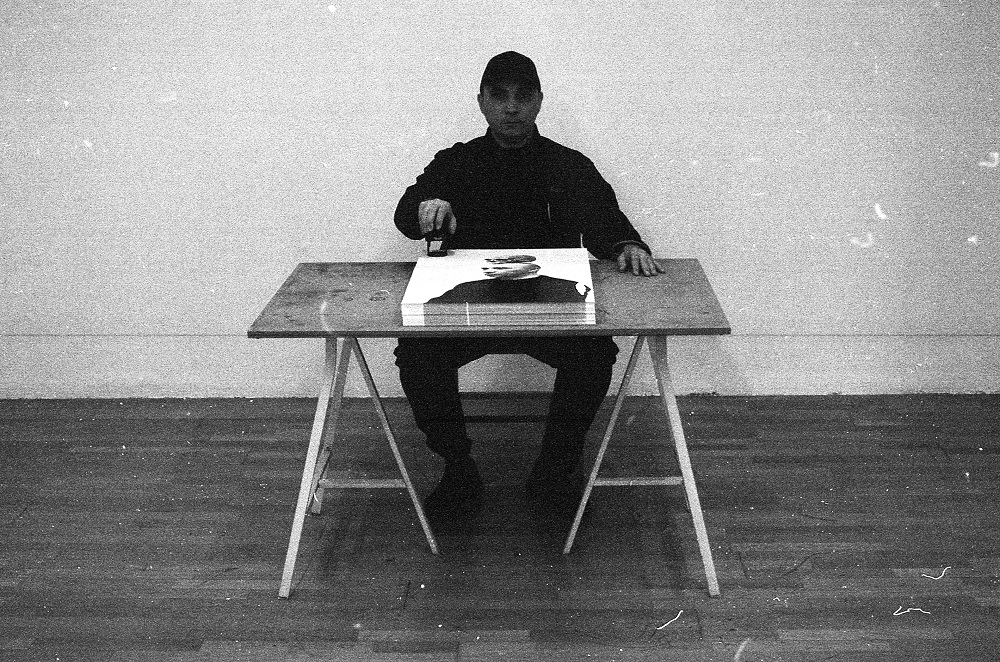

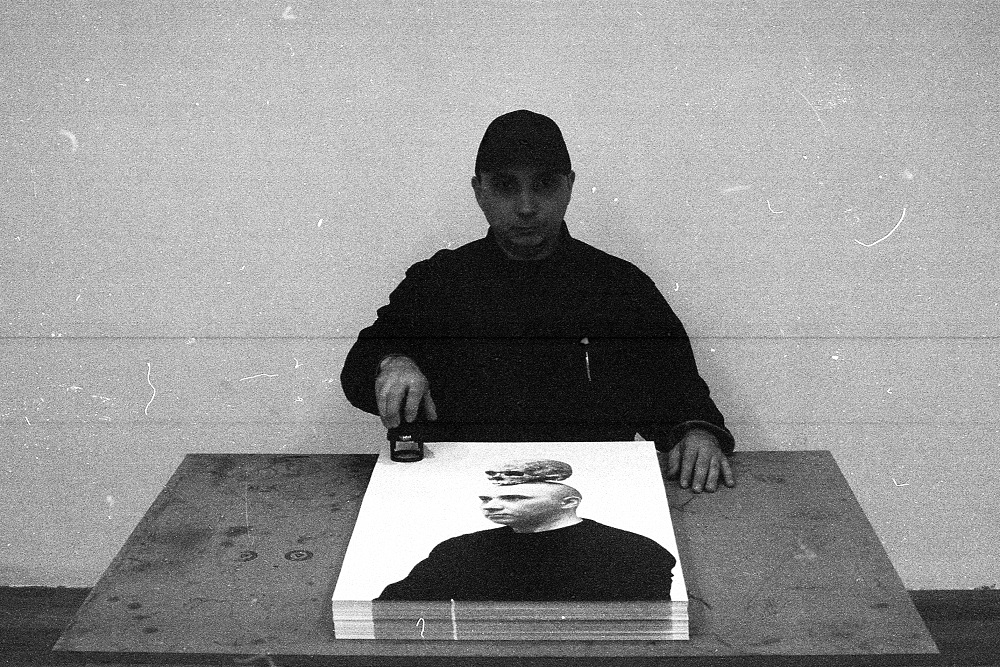

This exhibition (or perhaps better, an un-exhibition, since the show itself unfolds everywhere else) started from an image, the photograph taken by our mutual friend: a photograph entitled CP (campaignposterafterholbeincézannewarholetc.), 2025. It is a photograph of Lulaj with a human skull resting atop his head. No, ‘resting’ is the wrong word; ‘balanced’ is more precise. It is probably not surprising that Lulaj – an artist who has always been interested in levitation – should become the literal object that elevates a skull. But what is the skull? A mere art historical reference? This surely cannot be its content, or at least not the whole of its cosmology. In references, the skull would dissolve, but instead it remains quite resolutely atop the artist. How much does the skull weigh, I wonder? Is that weight some measure of the hidden forces here, of the violence that seems to keep some artists confined to birdcages, and keeps others doing the work of thieves? After I met Lulaj, he shared this image with me. I spent some time with it, trying to parse the gaze of this skull, and I think that I found something there that has given me a different view of Albania than I first had. Maybe the question is not about its weight, but about what it can see. The skull poised atop Lulaj’s head can even look into the eyes of giants, a mirror held up to the abyss. Eye to eye with emptiness, the skull seems to make a promise.

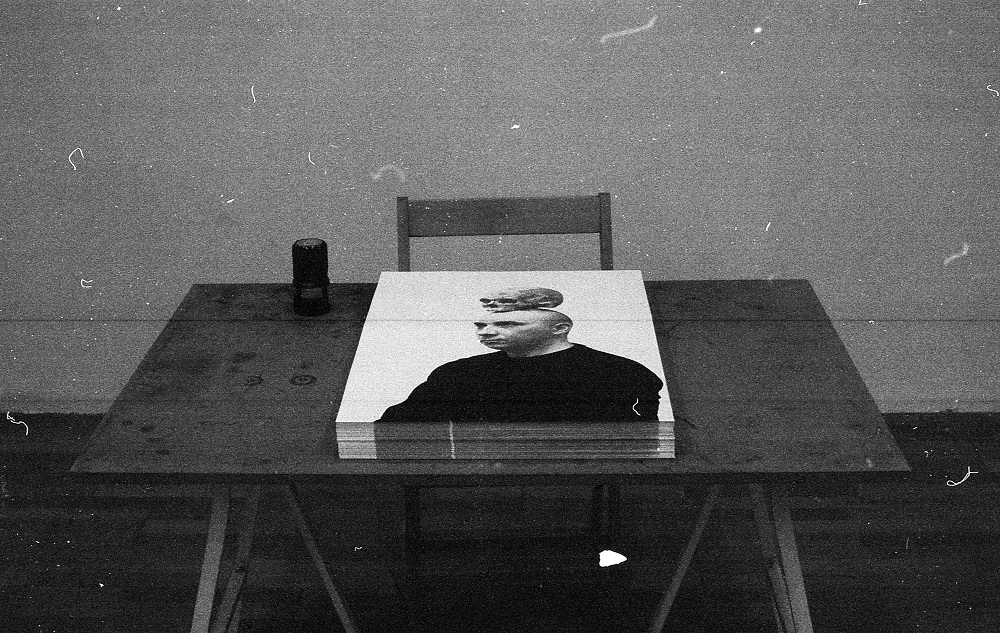

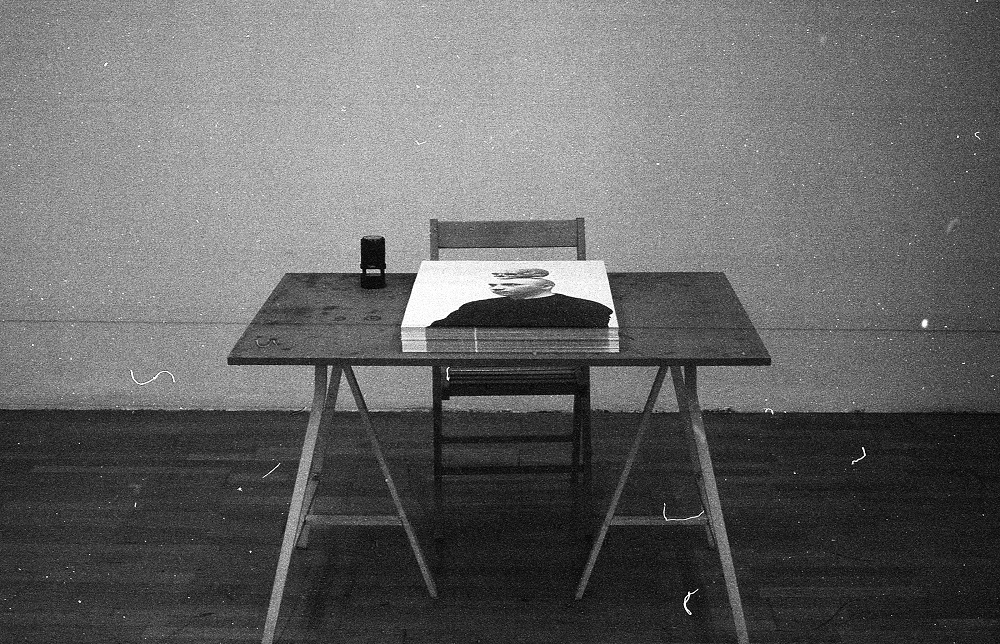

The photograph, I must say, is a very beautiful photograph, in black and white: it has the striking quality of a powerful artist portrait, and if it were only that, then perhaps it would be enough to entice you, my dear visitors, to pick one up, if only for the novelty. But today, on this day – 11 May 2025, from 7:00am to 7:00pm – this gallery is not a gallery, and this is not just an artist portrait. As the title of this exhibition suggests, today this space has been transformed into a polling station, like so many others open in Albania at this precise moment. And as in every polling station, here you will find ‘electoral’ material: this photograph serving as the poster for a hypothetical campaign. Like every good electoral poster, it tells a story. A story whose answer can only be found inside the ballot box, and then revealed when the ballot boxes are opened and the results are announced. A poster that is also a ballot, the image that escapes the world, only to end up in a box from which it will one day soon escape again. And why shouldn’t this image end up in ballot boxes? The skull atop Lulaj’s head knows better than to trust politicians, with their own piles of skulls, carefully crafting the mirrors that will reflect even deeper abysses. The country is already preparing for the spectacle of these mirrors.

Certainly, you may see this poster later (or maybe you have already seen it) in some alleyways across the city. Maybe some devious passerby already handed you this image, or told you where to come to get a copy for yourself: and now you know the stakes of the game. Today this gallery space is something different, a place where risks are amassing. Spaces like this could be the spaces that are really needed in Albania: the space for a general strike, the space for an exorcism – or perhaps better, for a seance. You might have come, like me, because you were looking for the promise of utopia, for the way-station – and just when it seemed you had found it, the dream was suddenly interrupted, as if someone whispered in your ear and you began to toss and turn and woke up feeling that you hadn’t slept. (This feeling hasn’t left me, personally, since I departed from Rinas, some weeks ago now.)

Or maybe you came because you were curious to see if the ghosts would reveal themselves in this room, this site of remote viewing: maybe the skull from atop Lulaj’s head would come alive and read a speech, language returning to a mute thing. But there are no speeches here except the ones that belong to the future, that can’t yet be written. Can’t be written? Who can stop them? Perhaps, beyond the empty eyes of giants, the skull can also see the high water mark, the cresting rise of the Great Wave.

Title: CP, Author: Armando Lulaj, Medium: Performance, Year: 2021, Courtesy of DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art & Zeta Contemporary Art Center

Title: CP, Author: Armando Lulaj, Medium: Performance, Year: 2021, Courtesy of DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art & Zeta Contemporary Art Center

Title: CP, Author: Armando Lulaj, Medium: Performance, Year: 2021, Courtesy of DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art & Zeta Contemporary Art Center

Title: CP, Author: Armando Lulaj, Medium: Performance, Year: 2021, Courtesy of DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art & Zeta Contemporary Art Center

Title: CP, Author: Armando Lulaj, Medium: Performance, Year: 2021, Courtesy of DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art & Zeta Contemporary Art Center