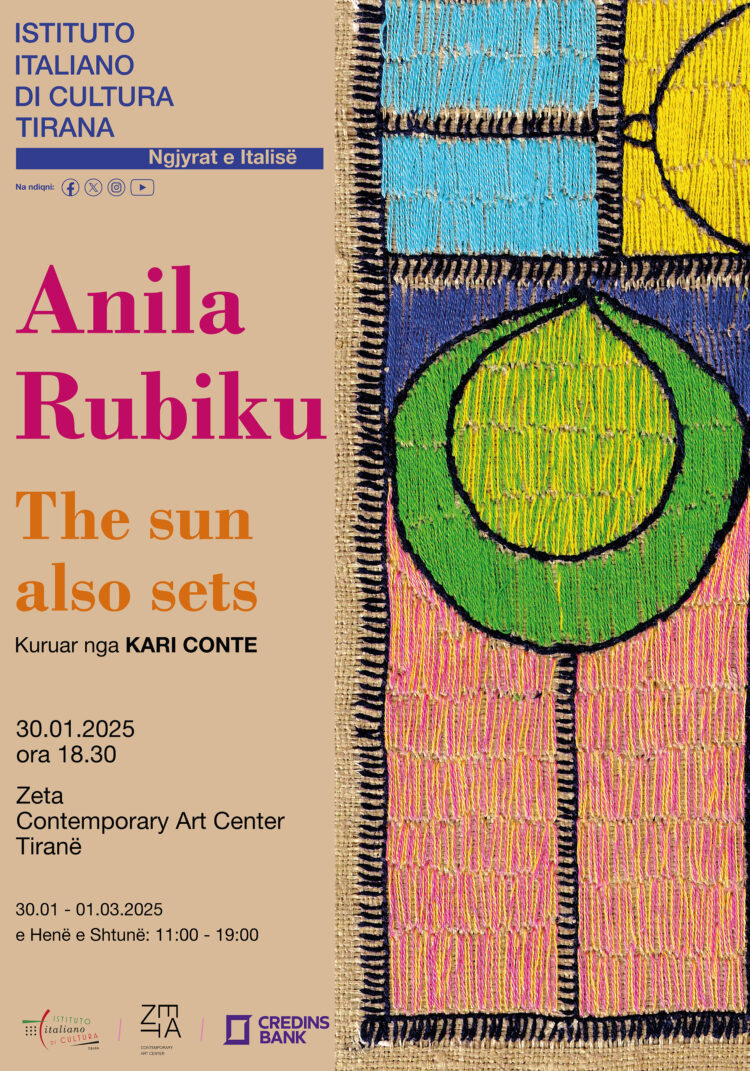

Anila Rubiku

The Sun Also Sets

Curated by Kari Conte

Opening Thursday, January 30 at 18:30

January 31st – 1stof March 2025

ZETA Center for Contemporary Art, Tirana in collaboration with Istituto Italiano di Cultura

The Sun Also Sets is Anila Rubiku’s first solo exhibition in Albania and contemplates impermanence, power, and the cyclical passage of time. Inspired by Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1818 poem Ozymandias, Rubiku reflects on the hubris of rulers who attempt to immortalize their legacies in public spaces, only to see their grandeur erode with time. The exhibition’s title draws on the fact that even though landscapes change, the sun will always rise and fall above them.

The exhibition presents sixty of Rubiku’s intricate drawings, etchings, and watercolors documenting the transformation of Albania’s urban and rural landscapes, particularly in Tirana and Durres. These works on paper—created between 2016 and 2018 and exhibited for the first time at ZETA—trace a century of corruption and shifting political powers through the statues, monuments, and architecture linked to the regimes ofEnver Hoxha, Joseph Stalin, and Vladimir Lenin. Through rigorous archival research, Rubiku reconstructs the history of emblematic sites like Skanderbeg Square and Liria Square, shaped by Ottoman, Italian, and Soviet architectural influences. These places bear the imprints of Albania’s past, reflecting what has been preserved and erased.

InThe Sun Also Sets, Rubiku depicts the towering symbols of power once built to assert control, revealing how these structures are as transient as the regimes they symbolize. Her work focuses on these contested sites, where remnants of history and ideologies coexist—often uneasily—within the landscape. Today, these spaces are altered by modern development that frequently favors profit over the preservation of historical and archaeological heritage, further complicating these charged sites of memory.

AnilaRubiku (Durres) is an Albanian born Italian artist, trained at the Tirana Art Academy (1994) and the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera (2000). She currently works between Milan, Toronto and Durres. Her work, intimately connected with political and social issues, uses various media: installation, sculpture, embroidery, engraving, painting. In her works, she addresses issues of gender inequality and social injustice with a poetic and ironic slant (Vierzon Biennale, 2022, Havana Biennale, 2019, 5th Thessaloniki Biennale, 2015), touching on environmental (Kiev Biennale, 2012) and relational issues (56th October Salon, Belgrade, 2016), reflecting on the meaning of being an immigrant today (Venice Biennale, 2011, Hammer Museum residence, Los Angeles, 2013) and on the relationship between the city and democracy (Venice Architecture Biennale, 2008).

Her work is part of the following private and public collections: Frac Centre-Val de Loire, France; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA; Mint Museum, Charlotte NC, USA; The Israeli Museum, Jerusalem; Deutsche Bank Collection, London, UK; Edition5 Collection, Erstfeld, Switzerland, P.O.C.Collection, Belgium,Brussels. National Museum of Women in the Arts (Washington DC);

She was nominated in 2014, by the Human Rights Foundation for her social commitment and was selected as one of the top Global Thinkers by Foreign Policy Magazine.

Kari Conte ( New York). Lives and works in New York and Turkey.

She is a curator and writer focused on global contemporary art. She has curated over forty exhibitions and regularly contributes to scholarly books, exhibition catalogs, and magazines. She serves as consulting curator for City as Living Laboratory (CALL) and as Senior Advisor at the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York, where she previously held the role of Director of Programs and Exhibitions from 2010 to 2020. In addition, she is Residency Curator for Kai Art Center in Tallinn, co-founder of Rethinking Residencies, and was a Fulbright Senior Research Scholar in Istanbul in 2021 and 2022.

As a writer, she is interested in the intersection of art, politics, ecology, and feminism as well as institutional and exhibition histories. She published Seven Work Ballets, the first monograph on artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles (Sternberg Press, 2016) and has contributed to numerous other books and exhibition catalogues.

Aporia of the Monument: AnilaRubiku’s The Sun Also Sets

RainoIsto

I. FOOTPRINTS

“There exists a death wish deep within the monument…” – New Red Order[1]

One of the most significant images of Tirana’s Skanderbeg Square was taken in 1991 by a photographer named Thomas Szlukovenyi. Looking northeast, Szlukovenyi’s photo shows the Albanian capital city’s square, populated by small groups of pedestrians passing across its expanse, and beyond it the clean horizontal geometry of the Palace of Culture and the rising mass of Mount Dajti in the distance. It is the picture’s foreground that is most striking, though.Immediately before the viewer is a concentrated abyss of monumental absence: a low pedestal with two massive, conjoined holes rent in its metal surface. The raking sunlight casts some of the exposed open interior of the pedestal into absolute darkness, a blackness deeper than any other shadow in the photograph. The photograph has been captured to emphasize the open space surrounding this scene of monumental trauma—no figures congregate in the vicinity of the pedestal, though of course we know the photographer stands just back from it, as if on the verge of a precipice.

The two holes in the surface are the footprints left by a monumental bronze statue of Albania’s dictator, Enver Hoxha—a statue that had stood atop the pedestal until late February of 1991, just weeks before Szlukovenyi took the photograph. This statue of Hoxha—created by sculptor Shaban Hadëri and painter SaliShijaku, and inaugurated in 1988, three years after the dictator’s death—had dominated the square only in the final years of state socialism in Albania, but the echo of its absence indexed by the photograph somehow suggests a much longer history. The torn metal edges of these massive footprints bear witness to the violence of the removal of Hoxha’s statue, which was torn down by protestors. It was one of many similar monuments to fall across the former state socialist world as communism disappeared as a horizon of possibility in the late 1980s, replaced by the promises of the free market and democracy (which would in turn usher in the harsh realities of shock therapy, and the eventual consolidation of neoliberalism in the region). In Szlukovenyi’s photograph, it seems possible to glimpse the importance of the emptiness at the heart of the period of so-called transition, a gaping hole that first swallows history before anything new can emerge.

This image of monumental absence appears again—now remade as a watercolor painting in modest dimensions—as part of AnilaRubiku’s expansive project The Sun Also Sets, which comprises several interrelated series of graphite drawings, watercolor paintings, and dry etchings that all circle conceptually around questions about the rise and fall of monuments, their relation to the urban fabric, and the kinds of historical experience they engender. Focusing on Albania’s capital, Tirana, and one of its major port cities, Durrës, The Sun Also Sets takes inspiration from the famous sonnet “Ozymandius,” written by the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in the early 1800s. Inspired by a remnant of a sculpture of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II (known in Greek as Ozymandius), Shelley’s now-iconic poem chronicles the ruins of a great sculpture of the eponymous ruler as they linger forgotten in the desert, a succinct metaphor for the way that even the greatest protagonists and events are eventually lost to the sands of time and history. Rubiku’s projectunpacks the repeated attempts to remake Albanian history and public space, chronicling the layering of interventions in the Albanian landscape (and cityscape) from the period of Italian fascist control and occupation, through the state socialist period and forward to the present day.

As its title suggests, The Sun Also Sets—like Shelley’s poem—explores the cyclical character of temporality: statues, buildings, and public plazas appear, disappear, and reappear again across the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, as Rubiku reimagines photographs documenting these changes, creating a new archive of history in flux. The project is anchored to Shelley’s poem by a series of dry rubbings in colored pencil that reveal snatches of the sonnet’s text through organic, abstracted—though sometimes suggestive—forms. In dialogue with these abstracted forms, the remainder of the images that collectively comprise the project present legible urban ensembles that shift over time: viewers encounter both meticulous pencil renderings that suggest the purportedly objective character of photographic indexicality (though of course photographs in state socialist times were famously often doctored, retouched and embellished for readability and ideological clarity), and watercolor images whose more amorphous aesthetics and sinuous lines suggest the intervention of human emotion overlaying the built environment. In these scenes, slogans appear and disappear from buildings (such as the words RROFTE R.P.S. E SHQIPERISE—Long Live the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania—from the roof of the Durrës town hall), monuments replace oneanother (the monument of Stalin that once stood in Skanderbeg Square replaced in 1968 by the equestrian statue of the national hero Skanderbeg, who still stands in the square today), and tall apartment buildings spring up around and over archaeological sites (as the in the case of the Durrës amphitheater or the city’s Venetian tower, now surrounded by new developments).

II. THE MONUMENTALITY OF LIFE

One of the most paradoxical characteristics of monuments is the way that we associate them with both vast stretches of time immemorial—their ruins indicating a history so old we cannot grasp it—and with the cycles of perpetual renewal that accompany modernization. Despite the sociologist Lewis Mumford’s famous claim that “The notion of a modern monument is veritably a contradictionin terms,”[2] monument-building enterprises have accompanied virtually every effort to transform society in the modern era. Even as theorists have insisted on the fleeting and ephemeral character of life in modernity—defined by ever-shifting frames of reference, radical alterations of both the psychic and the built environment—monuments have persistently sprung up, their apparent longevity belying the rapidity of the transformations that surround them. In modernity, even the most enduring symbol can disappear overnight, demolished to make way for some new configuration of the city. But so too can the most violent upheavals of everyday life be soothed by the inauguration of some new, supposedly lasting image: a historic figure, a commemorative ensemble—something to insist that memory will endure, that all will not be washed away by the waves of change.

The massive scale of monumental transformation was a fundamental aspect of fascist Italy’s colonization of Albania, including the master plan for Tirana, with its long north-south axial boulevard (now called the “Martyrs of the Nation” boulevard) projected by Armando Brasini, which was later significantly developed by GherardoBosio (who focused primarily on the southern half of the boulevard, then called the Vialedell’Impero).[3] If fascist colonialism and occupation shaped some of the major cities of Albania, including its capital, then the socialist period would see an even further development in monumentality as a tool for modernization in Albania.

Monument-building was an important aspect of socialist Albania’s consolidation of its symbolic power, and its insistence that a revolutionary new way of life had been achieved after the National Liberation Struggle and the defeat of fascism. The monument-building boom reached a peak in the late 1960s (partially coinciding with the 25th anniversary of the country’s liberation from fascist forces in 1969), and the proliferation of monuments transformed Albania into what artist and critic KujtimBuza(writing in 1973) called “a landscape of stone, of marble, a landscape of bronze.”[4] This memorial landscape turned the country itself into a text that could be read, a history projected across the territory with episodes ranging from Skanderbeg’s medieval struggles to the National Awakening period, through the Partisan antifascist resistance and into the present day and the building of socialism. In this new landscape, monuments played a multifaceted role: one of socialist Albania’s most prominent monumental sculptors, MumtazDhrami, wrote in 1976 that when we encounter monumental works, “we pause to think, we take our oaths, we pass by, we stop to rest. Monuments have created an active aesthetic association between the working masses and the environment that surrounds them.”[5] This active aesthetic association was part of what Dhrami’s colleague and frequent collaborator Shaban Hadëri called “the monumentality of our socialist life.”[6]

It was not simply the built environment, then, that was monumental: it was socialist reality itself, which was supposedly developing at a pace unheard of under previous regimes. Life under state socialism became a kind of totalized aesthetic experience,[7] and the Albanian people were supposedly reconfigured into the “sole creative subject”[8] of this new aesthetic phenomenon. And indeed, after the end of state socialism in Albania, in many cases the Albanian people continued to act in their capacity as creative subjects—or in some cases, destructive subjects—repurposing the official buildings of the socialist era (which had often already been repurposed or adapted), undertaking informal modifications of architecture, and removing official symbols of the socialist regime. But the transformation of public (and private) spaces that took place in the 1990s was not solely driven by the populace at large—it was also driven by new government initiatives that sought to remake the fabric of cities, but even moreso to remake the relationship between the government and its citizens.

One of the most famous of these interventions is the intervention made by the Edi Rama in the early 2000s in Tirana (when he was the mayor of the capital city; he is now—since 2013—Albania’s Prime Minister). The son of another of Albania’s best-known monumental sculptors, Kristaq Rama, Edi Rama is an artist himself, and in his years as Tirana’s mayor he became widely known in both international political and artworld circles for undertaking a project to paint many gray concrete apartment buildings in bright colors and abstract geometric patterns. Rama described this project—in the video work Dammii Colori (Give Me the Colors, 2003) created by his friend and frequent collaborator, Anri Sala—as “not an outcome of democratization,but more an avant-garde of democratization.”[9] In a sense, Rama’s project to re-imagine the façades of the capital city is a continuation of the socialist-era project to remake reality, but now the political leader is placed at the center of this change: it is the artist-politician who leads the “avant-garde of democratization,” rather than the (socialist) citizen who takes up the role as the “sole creative subject” of a new life.

The Sun Also Sets is sensitive to these shifts in how the agency to transform the world has shifted over the past century, documenting not only the idealization of the socialist worker (in a pencil drawing of a bronze sculpture by none other than Kristaq Rama, part of the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Tirana), but also Edi Rama’s painted façades project, which she captures in two watercolor images dated from 2001 and 2018, respectively. Across 17 years, we see the fading of Rama’s colors, even as we also see the radical transformation of Skanderbeg Square (another project in which Rama sought to intervene in a long chain of historical alternations) into a vast empty space, its desert-like surface broken only by fountains that spill water across its new, slightly sloped pyramidal expanse. On the one hand, the scale of this change seems inhuman, but it also redirects our attention to the small stories that unfold in the midst of these changes.

III. SHROUDS

“When Stalin appeared on the horizon, I knew I would be safe.”—Lea Ypi[10]

Indeed, many of themonuments that appear in The Sun Also Sets tell particularly noteworthy stories: for example, take the bust of Stalin that appears in Liria Square in Durrës, in front of the Great Mosque, in one of Rubiku’s pencil drawings. This is the same image of Stalin that Lea Ypimentions in the opening episode of her recent book Free, wherein she describes a moment from her youth, in late 1990s, a day when she clung to the Stalin monument while a crowd of protestors chants “Freedom! Democracy!,” marching through Durrës’ streets(only to later look up and discover that Stalin’s head is missing, presumably taken by the protestors). But in Ypi’s account, either through an intentional introduction of fiction or through a profound misremembering of the events, the Stalin to whom she clings is not the bust that stood in Durrës, but rather the full-length bronze statue of the dictator that had once stood in the center of Tirana,[11] a gift from the Soviet Union during the period of alliance between Albania and the USSR. (Ypi vividly recounts Stalin’s hand thrust within his coat, and pressing her cheek to Stalin’s thigh, struggling to encircle his knees. But of course this could not have been the Stalin bust that stood atop a pedestal in Durrës.) Ypi’s fictional reconstruction of this moment transforms her book into a concise metaphor for her own early struggles with change, on the cusp of Albania’s transition from state socialism to free market capitalism—but it also undoes the complexity of reality, turning it into a narrative far more palatable for international audiences, who never experienced Albania’s socialist period. The fact that Ypi resorts to fiction precisely in the case of the Stalin statueactually points to a key aspect of monuments: despite their supposedly imposing presence and ideological clarity, they are uniquely vulnerable to becoming the centerpieces of attempts to revise history.

It is not so much that monuments disappear from our notice (though novelist and philosopher Robert Musil once famously wrote that ““there is nothing in this worldas invisible as monuments”[12]), as that they form the nexuses around which forgetting and rewriting congeal and cohere. The bust of Stalin in Rubiku’s pencil drawing thus marks not only an episode of ideological commitment—though Albania indeed did remain the staunchly committed to a Stalinist line long after other nations of the socialist world had re-evaluated that legacy—but also a point where memory and meaning are contested, where the monument emerges as something both fallible and vulnerable.

A similar episode of vulnerability appears in another image from The Sun Also Sets, this one showing the gathering of bronze statues placed behind Tirana’s National Gallery of Art (where many of them remained until renovations began on the building a few years ago). For years, this collection of sculptures—including the Stalin statue that had once stood in Skanderbeg Square, a bust of the partisan Liri Gero, a bust of Enver Hoxha, and Kristina Koljaka’s sculpture of Lenin (one of the few works of monumental sculpture created by a woman artist in socialist Albania)—had been arranged behind the museum. Some had been moved there from the former site where sculptures were cast in bronze under socialism, and at one point several of the sculptures were covered with tarpaulins (presumably partially in response to an incident in 2012 in which an anonymous artistic groupcalled the “Ag Collective” painted the Stalin and Lenin sculptures red[13]). Eventually the sculptures were uncovered again, but Rubiku’s watercolor images capture them shrouded in white tarps, their identities obscured and their gestures uncertain. One of the figures thus shrouded is OdhisePaskali’s statue of Stalin that once stood at the entrance to the Stalin Textile Factory in the Kombinat neighborhood, where it welcomed workers with a beneficent gesture, Stalin’s right arm extended as if in blessing. (The monument appears, famously, in AbdurrahimBuza’s 1949 painting Volunteer Work in the Stalin Textile Factory, where it rises above a laboring sea of men, women, and children.) The shrouded figure that appears in The Sun Also Setsis not even legible as Stalin—though we do catch a glimpse of his long trenchcoat emerging from beneath the white tarp—nor is his welcoming gesture readable any longer. At his feet is the wrapped bust of Hoxha, which also appears as the sole subject of another of Rubiku’s watercolors. The wrapping of these figures is paradoxical since it suggests that it is them that need to be made safe from us as much as we need to be protected from their impact.

A final episode of remaking documented in The Sun Also Sets demonstrates the nuance of the projects engagement with Albania’s history. As part of the series of images documenting the fall of the statue of Enver Hoxha in Skanderbeg Square, Rubiku has also taken viewers further afield, to the slopes of Mt. Shpirag, near the city of Berat in southern Albania. There, in 1968, during the period of Albania’s Ideological and Cultural Revolution, soldiers from the People’s Army worked alongside socialist youth to paint the dictator Enver Hoxha’s name, ENVER, on massive stones draggedto the mountainside from the surrounding area, in letters large enough to be visible from the valley below (and from the Mao Zedong Textile Factory, built with the aid of Chinese engineers, in the spirit of socialist internationalism).[14] This massive geoglyph appears in one of Rubiku’s pencil drawings, but it is paired with a watercolor image that shows a significant transformation of this monumental inscription: across Shpirag’s foothills we see written not ENVER but NEVER.

In the early 2010s, Albanian artist Armando Lulaj began investigating the ENVER geoglyph, which had been almost completely obscured by overgrowth (and further degraded by attempts made in the post-socialist period to destroy the letters). Lulaj set out to remake the geoglyph, switching the position of the first two letters so that it now reads NEVER(which in turn became the title of a video project that Lulaj presented in the Albanian Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, one of three projects Lulaj collectively titled the Albanian Trilogy).[15] In an interview about the project, Lulaj declares that the remaking of the monument is not a negation of the dictator’s name, but rather a reflection on the new “condition of absolutism”in neoliberal capitalism, an absolutism that wears the “guiseof democracy,” espousing the notion that democracy “includes all possibilities.”[16] Elsewhere, Lulaj explains that at the time he created NEVER, he told his collaborators, that “this work, thoughso emphatically visible, would only start being perceived afterten years or so, or perhaps will only really be perceived when itbegins to disappear, when it will once again be covered by time.”[17]

Rubiku’s inclusion of the rewriting of the geoglyph

in Berat seems to understand precisely this temporal paradox of perception: that

so many monuments, in their numerous iterations and remakings, are messages

that can be perceived only in some future moment, and perhaps precisely in the

moment when we can no longer see them clearly. It is this paradoxical future

sight that the whole of The Sun Also Sets promises,

as collection of images that move back and forth across time. Perhaps, they

speak to us from the moment when the sun rises again, or sets again, as it does

in what can only be read as the “final” image in The Sun Also Sets: a

fiery, colorful sunset over the sea in Durrës, captured in 2018. From the empty

footprints of the dictator’s statue to a sky awash in color: a memory displaced,

already fleeting.

[1] This line appears in a video projection by the public secret society New Red Order, (NRO) a group that includes Adam Khalil and Zack Khalil (Ojibway), and Jackson Polys (Tlingit). The video was recently shown as part of NRO’s exhibition project Feel at Home Here at Artists Space in New York City, 2021: https://artistsspace.org/exhibitions/new-red-order.

[2] Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1938), p. 438.

[3]Elidor Mëhilli, From Stalin to Mao: Albania and the Socialist World (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017), pp. 25–27.

[4]Kujtim Buza, Kleanth Dedi, and Dhimitraq Trebicka, Përmendore të Heroizmit Shqiptar (Tirana: Shtëpia Qëndrore e Ushtrisë Popullore, 1973).

[5] MumtazDhrami, “Vendosja në hapësirë dhe përmasat kanë shumë rëndësi,” Nëntori vol. 23, no. 4 (April1976): p. 23.

[6]Shaban Hadëri, “Monumentaliteti i jetës sonë dhe pasqyrimi i tij në skulpturë,” Nëntori vol. 24, no. 5 (May 1977): pp. 246–248.

[7] Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (New York: Verso, 2011).

[8] Alfred Uçi, “Vendi i artit popullor në kulturën artistike socialiste”, in Uçi, Probleme të estetikës (Tirana: Shtypshkronja e Re, 1976), p. 15.

[9] Rama in Dammi i Colori, quoted in Vincent W. J. van GervenOei, “Give Me the Colors … and the Country: Albanian Propaganda in the21stCentury,” Art Papers, March/April 2016,https://www.artpapers.org/give-me-the-color-and-the-country/.

[10] Lea Ypi, Free: Coming of Age at the End of History (New York: Penguin, 2021), p. 3.

[11]Ardian Vehbiu, “Stalin on Demand,” Peizazhe të Fjalës, 30 May 2022,https://peizazhe.com/2022/05/30/stalini_imagjinuar/.

[12] Robert Musil, “Monuments,” in Selected Writings, ed. and trans. Burton Pike (New York: Continuum, 1986), p. 320.

[13]RainoIsto, “Mbi Artin Bashkëkohor në Shqipëri,” Peizazhe të Fjalës, 25 April 2016, https://peizazhe.com/2016/04/25/mbi-artin-bashkekohor-ne-shqiperi/.

[14]Raino Isto, “Between Two Easts: Picturing a Global Socialism in Albanian Postwar Art, 1959–69,” Art History 45:5 (November 2022): p. 1075.

[15] See Albanian Trilogy: A Series of Devious Stratagems, ed. Marco Scotini (Berlin: Sternberg, 2015).

[16] Armando Lulaj, “Interview with Armando Lulaj,” Public Delivery,2014, http ://publicdelivery.org/armando-lulaj/#arve-load-video. See also RainoIsto, “‘Weak Monumentality’: Contemporary Art, Reparative Action, and Postsocialist Conditions,” RACAR: Journal of the Universities Art Association of Canada 46:2 (2021): p. 48.

[17] Armando Lulaj and Marco Mazzi, Broken Narrative: Politics of Contemporary Art in Albania (Punctum, 2022), p. 45.