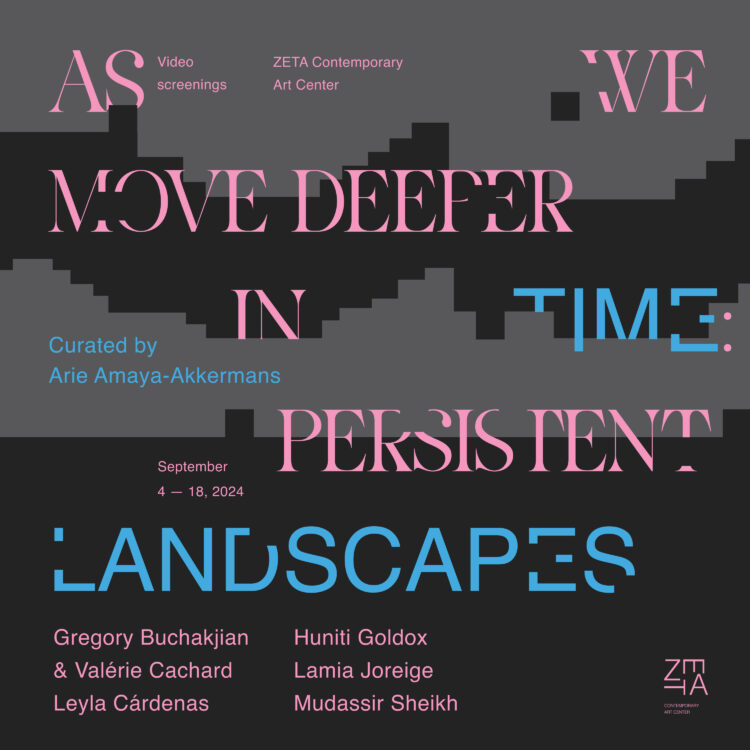

AS WE MOVE DEEPER IN TIME: PERSISTENT LANDSCAPES

Video screenings

Artists: Gregory Buchakjian & Valérie Cachard / Leyla Cárdenas / Huniti Goldox / Lamia Joreige / Mudassir Sheikh

Curated by Arie Amaya-Akkermans

ZETA Contemporary Art Center

September 4-18, 2024

The concept of ‘deep time’ in archaeology is as old as the idea of antiquity, born in the 1860s, but it has become widespread today in ecology and landscape archaeology, due to the impact of GIS (geographical information systems), and LiDAR images (light detection and ranging), identifying previously unknown features of archaeological sites, using a combination of archival and public domain images and artificial intelligence. In landscape ecology, we hear often that due to the ‘time depth available from the archaeological record’, long-term processes can be studied at a variety of temporal and spatial scales. But what exactly archaeologists mean by ‘time depth’ is far less understood. Chilean archaeologist Cristián Simonetti wrote in 2014 that, as we move deeper in time, we do not know with precision which direction is implied in this depth: Is it running downwards, moving backwards, going up vertically, or moving forward?

The passage of time is well conceptualized in stratigraphy as a vertical column, but does this time column move from top to bottom or the other way around? What happens when the time is out of joint, and the layers become inverted, or suddenly go missing? The video screening series is inspired by Colombian artist Leyla Cárdenas’ video ‘Interpretation of Deep Time, First Attempt’ (2017) that articulates time as a multidirectional function of the real, physical space. In the video, the upside down view of a rammed earth wall in the outskirts of Bogotá, is a physical stratigraphy of time, not simply as a result of erosion, but of spatial and environmental violence. The traces of human violence and destruction now have geological qualities that have left permanent marks in the landscape. For Cárdenas, the wounded landscape is not simply a site of damage, but also a historical and political condition of disorientation that unmakes any simple passage between past and future.

In the series, “As We Move Deeper in Time: Persistent Landscapes”, we will be looking at video practices in conversation with Cárdenas, that examine the problem of directionality in time, but not in the abstraction of linear or metrical time, but rather, embedded in complex assemblages between nature, culture, history and time, with a particular eye on postcolonial landscapes. Either landscapes that stand for arenas of reflection for the experience of political violence, or landscapes that themselves have become rapidly changed by aggressive transformations. In his book, “Making Time: The Archaeology of Time Revisited” (2021), Gavin Lucas wrote, partially in response to Simonetti, that movement in time is not only chaotic and unpredictable, but it can also become suddenly multidirectional, pushing in different directions at the same time, stretching temporality, and sometimes suspending it or collapsing it. Nature becomes a site of tension, paradox and discontinuity.

Starting out with a conversation that began in the UNIDEE residency “Neither on Land Not at Sea”, at Città dell’Arte – Fondazione Pistoletto, around the topic of water, Pakistani artist Mudassir Sheikh, reflects on the relationship between bodies of water, environmental damage and violence. In his short film “Going Inwards” (2023), he focuses on Sufi shrines and their proximity to the water, exploring both indigenous healing practices in Pakistan and the collective trauma of a country where capitalist exploitation and environmental damage has caused both a scarcity of water and endemic floods. In Sheikh’s video practice, the waters continue reclaiming their ancestral territory, contesting geopolitical borders and eroding the ephemerality of Cartesian, metrical space. Time depth appears here as a formless, viscous substance with corrosive powers, melting the smooth surfaces of linear spaces, at different, often overlapping speeds.

In their practice, artist collective Huniti Goldox (Jordanian artist Areej Huniti and German artist Eliza Goldox), mentors of the module ‘The Rise and Fall of Water’ at UNIDEE, have researched the intersection between political systems, violence, bodies of water and landscapes. Their video, “As Dust, As Rain, as a Line on the Map and a Crack on History” (2022), part of a project first developed in Tirana, provides a link to the local context: Set in Albania, the work explores the pollution in the “Tirana” River, from its source in Mt. Datji, proposing a speculative, para-fictional narrative, set in the future, in which the river thrusts upwards in the form of a tower. The video emphasizes the city as a complex organism that often experiences systemic shock and change, thinking back to the Tirana earthquake in 2019. Both Huniti Goldox and Sheikh engage with deep time through mythology, postcolonial historiography, aquatic memory, and the critique of capitalist accumulation.

In the second conversation, taking place between Lebanese artists, we are in the presence of the sublime as a form of deep time, in the hilltops around Beirut and the Aegean islands in Greece, as geological landscapes that serve as narrative containers for an interface between traumatic memory and poetry. Both works were completed in the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion of August 4th, 2020, but yet go back into different past scales simultaneously. A short film by Lamia Joreige, “Sun and Sea” (2021), produced in collaboration with the late poet and painter Etel Adnan, is set on the rocky landscape of the Aegean, as a metaphor for deep time, is based on Adnan’s first poem written in 1949, and a series of decades-long conversations between Joreige and Adnan, juxtaposing the pure and timeless geography of the islands of Greek myths, against the background of unceasing violence in Lebanon and Palestine, paradoxically so close by.

The video opera, “Agenda 1979” (2021), is a collaboration between artist Gregory Buchakjian and writer and playwright Valérie Cachard, originally produced for the Opéra National du Rhin and presented online during the pandemic, is a story centered around a Palestinian fighter’s diary found in a bombed-out Beirut apartment during the Civil War, but telling of a multitemporal narrative of violent conflict and grief in Lebanon. Yet, it is set on the arresting landscape of the mountain peaks above the city, contrasting a history of warfare and destruction, beset with transience, change and constant movement, against the timeless surroundings. Departing from Buchakjian’s signature visual archaeology of war architecture in Beirut, the work takes a leap into the purely sensorial, conjuring up an experience of time that moves back and forth in the space of memory, and formulates a time that is not an abstract silent background but a porous surface co-created by objects, events, memories and places.

Exhibiting in Tirana these reflections about political violence, either inflicted on the landscape directly, or re-interpreted through the natural sublime, anchors the question of time depth in a city undergoing brutal social, economic and political transformations, and which might become eventually not only unrecognizable, but also unrememberable. The ability of the moving image to use time as a physical force and sculpt it, even if only temporarily, connects history with non-human elements as a continuous assemblage of materials, archives and present ruins. With a greatly expanded notion of historical time, inherited from archaeology, the distant past of nature might reappear in relative proximity to the political present, and crucially overlap. Simonetti has called this process, ‘feeling forward into the past’: “Concepts of time are not abstract entities, fixedly stored in the mind, but sentient acts of conceptualization that depend on the dynamic field of forces in which things and people become entangled.”